Over the course of Winter Semester 2023 at Oakland University, I had the privilege to learn about Native authors and the continual fight they undertake to reduce the harmful effects of erasure—the colonial narrative that functions to erase Native history and presence—in American society. By listening to these voices, I learned what it means to be unsettled by my own presence and history. It taught me the importance of power and whose narrative continually gets the spotlight. It’s important to question presumed ideas and perceptions about our society and analyze the constructed world in a whole new light.

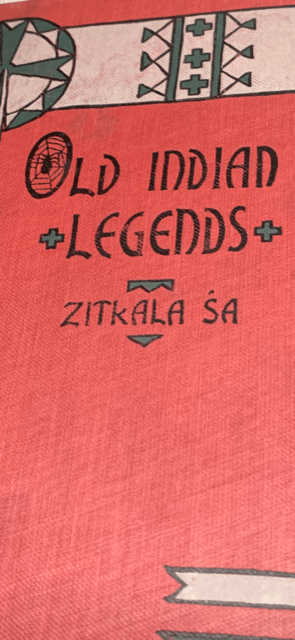

Of the many Native authors I had the pleasure of reading, Zitkála-Šá’s literature stood out to me in the dusty archives as a voice of today. Šá’s Old Indian Legends, along with her other works, continue to advocate for the sacred future Native peoples have been working toward for years. She unveils the true brutality colonists have subjected Native peoples to by discussing the cruel treatment in the boarding schools and sharing her own experience in such conditions. The physicality of her novel alone protects and reproduces traditionally oral stories of Dakota storytellers and in doing so she indigenizes the very act of colonial novel writing. Currently, Old Indian Legends, circa 1901, resides in the Archives and Special Collections of Kresge Library at Oakland University. To comprehend the significance of her work and the injustices it has endured, it is important to look at how the library has utilized its presence, how and who the library has acquired it from, and how—moving forward—the library should respect and circulate it. We must also question: What is her work doing in an archive? How does the Library of Congress catalogue assess and generalize such texts? How can an archive bury history?

Who is Zitkála-Šá? How did her work end up in Kresge Library?

Zitkála-Šá’s a Yankton Dakota author who has written various non-fiction, fiction, poetry and political works. My specific study centers around the 1900-1904 span with a special look at her collection Old Indian Legends published in 1901. Most notably, Ginn & Company (founded by Edwin Ginn in 1867) was known for publishing school texts in the City of Boston (Industry in Cambridge)1. I inferred that the reputation of the publishing house informs the specific use Šá intended for her audience. Using a publisher who specializes in school texts illustrates Old Indian Legends as a learning/educational tool for readers.

In addition to Old Indian Legends being published by Ginn & Company, the particular copy I examined is in the Thelma James Collection–one of the various collections that have been donated to Kresge Library. Her collection is known for holding folklore works from various countries and cultures. Oakland’s Kresge Library describes Dr. Thelma James on their “Special Collections” page as, “a professor at Wayne State University for many years” who “accumulated a large collection of folklore materials. Her donation of some 650+ volumes is strong on the folklore of various countries and on witchcraft.”2 Her collection emulates the work Šá aspires to – to help her audience learn more about cultures they didn’t personally grow up with. Zitkála-Šá explained in her “Preface” of Old Indian Legends, “The old legends of America belong quite as much to the blue-eyed little patriot as to the black-haired aborigine. And when they are grown tall like the wise grown-ups may they not lack interest in a further study of Indian folklore, a study which strongly suggests our near kinship with the rest of humanity” (VI).3 Šá wants her readers to find the similarities to other mythologies and to document these oral stories so that future children may learn more about their world. James’ donation continues to spread Šá’s wishes by allowing students like me to find Šá’s work and discover more from its pages.

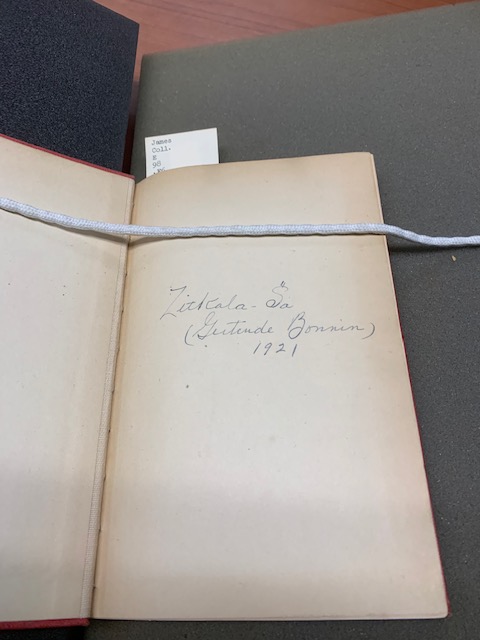

The more attention one gives to a book the more one finds to be learned. For example, in my research, my peer and I discovered that James’ copy of Old Indian Legends was a signed copy. We went through the process of researching and comparing multiple signatures to determine the authenticity. In the end, our Rare Books Librarian, Emily Spunaugle, helped us determine that yes, the signature was authentic. I’ve found that the institution of the archives is complicated and complex. In some ways it silences important voices of the past and greatly generalizes them. In others, it protects and preserves old collections so they can be read in the future and learned from. However, the archives can only function with the right audience to analyze and give attention to its books. My peer and I would never have been able to interact with and draw attention to this book if it wasn’t for our archive project demonstrating the importance of audience. It begs the question; how do we find the right audience for these works and how can the right audience revive an old book?

What are the institutional problems in the Archives? How do we find the right audience for Zitkála-Šá’s work?

The archives and special collections protect and collect old books that have “historical” significance. Basically, they’re meant to keep these books preserved in a climate-controlled area. Each of these books gets catalogued to make locating them easier. It is in this cataloging system that colonial history begins to rear its ugly head. I learned from (insert title here) Emily Spunaugle that to organize US libraries, librarians use the Library of Congress Classification System—a system that is slow to change and organizes books in predetermined categories. For example, Zitkála-Šá’s Old Indian Legends is catalogued as E 98. F6 Z48. As published on the official Library of Congress website, E 75-99 labels books under, “Indians of North America” (2).4 Looking objectively, this system groups all Native Tribes together refusing to acknowledge the differences between each governance. Not only does it generalize, but this category is situated next to “history” books and racist texts that promote violence and perpetuate colonial lies such as works by John Smith or Thomas Hariot. It also situates Native presence in the past instead of acknowledging current works by Native authors. While working on my archive project, I got to see firsthand the types of works that Zitkála-Šá’s resides beside—many of which were written by colonizers who controlled the narrative of early “discovery”.

Jean M. O’Brien—scholar of Native American studies—helped me identify the harmful narratives of colonizers. Specifically, her work explains the narrative of “firsting” and the “myth of Indian extinction” prevalent in settler-colonial texts (O’Brien 4). She explains, “non-Indians insisted that Indians could only be ancients, they could never be modern.” They believed that “Indians had vanished from their vicinities. The collective end product purified New England of its Indian past on the imaginative level” (5).5 Situating a collection like Zitkála-Šá’s Old Indian Legends in the past—supporting the extinction myth— undermines the purpose of Šá’s work, which functions to project oral legends into the future. Old Indian Legends doesn’t belong among “history” books and racist texts.

Not only does the cataloging system promote colonial narratives of “extinction,” but it also makes it harder for the audience to find the right books. There is a difference between the racist texts and Šá’s Old Indian Legends. The fact that they’re placed together undermines the function of an archive and a library in general. One of the first steps to cleaning up the institutional racism in archives and getting Šá’s text to the right audience is reexamining the Library of Congress and how it catalogs—important work that is ongoing by forward-thinking library practitioners in the field. More attention needs to be placed on decolonizing the Library of Congress to support the “sacred future” of Native cultures.

How does Old Indian Legends protect a “sacred future”? How does Zitkála-Šá utilize novel writing?

I first came into contact with the concept of a “sacred future” through the presentation of a Native seed packet. Professor Andrea Knutson presented this packet to us in class to demonstrate what it means to be against capitalism and colonial society. The seed packet legally binds the holder to a responsibility to the seed. That responsibility is defined in the contract printed on the seed packet flap: the holder can never sell the seeds for monetary profit once the packet is opened. These seeds themselves are special because they are unaltered by big corporations. My professor explained that by planting them in the earth one gives back and the more they grow the more they represent a future where Native culture gets planted as opposed to erased. Thinking in terms of metaphors, I’d like to paint Old Indian Legends as a seed Šá has planted. Her work preserves the stories of old just like the seed packet, making sure no one can corrupt or erase that culture.

Poet, author, and Lakota woman, Layli Long Soldier, explains it better than I can in her 2019 introduction to Zitkála-Šá’s American Indian Stories. Long Soldier writes, “she wielded her tools purposefully…to make a statement aimed directly at the forehead of colonialism” (XI). Long Soldier asserts perfectly that Zitkála-Šá didn’t accept the tools of colonialism willingly; she did it in order to shape them to her own use to protect that which was being erased. Throughout Long Soldier’s “Introduction,” it’s clear how much admiration and respect she attributes to Zitkála-Šá and she makes reference to how Zitkála-Šá’s stories have impacted her: “At times while reading I have to swallow, stop, and close the book. I must let her work rest, let my body rest, and enter again slowly. As a Lakota and as a woman, I feel a personal connection and literary lineage” (VII).6 Šá’s work continues to connect and inspire people today; it reaches to the bottom of one’s soul to project a connection. Zitkála-Šá has fostered a relationship with her reader through her work – it’s impactful and meaningful to modern Native communities in a way that other literature doesn’t quite measure up. That being said, how then do we address Zitkála-Šá’s place in the archives?

Where should Zitkála-Šá’s work reside?

It’s hard for me to answer this question as a non-Native person myself. It goes deeper than just suggesting that her work should be given back to those it was intended to protect as that would go against what Zitkála-Šá wanted her work to do. She didn’t just mean for it to preserve these stories; she wanted these stories to be a connection to other cultures as well – to demonstrate just how similar all our humanities are to one another. So then, what is the next step to honoring her work and supporting Native futurity?

I’ve come into a deep understanding of what it means to protect and support Native futurity—the movement meant to fight back against the “extinction myth” by setting Native ideas and traditions into future settings. One aspect of that involves reaching out to colonial descendants who are willing to be unsettled with the truth about their own role in the current constructed world. Afterall, do you know whose land you reside upon? Finding the colonial descendants who are willing to listen to authors like Zitkála-Šá, Layli Long Solider, and Jean M. O’Brien marks the first step to rewriting narratives like “discovery” and cementing the horrors of genocide the colonists made.

On the other side, futurity involves allowing Native peoples to continue practicing their cultural traditions without persecution. Recently, Oakland University has become responsible for the Native American Heritage Site on campus and holds a very unique opportunity to integrate teaching and reclaiming in one setting. For context, rematriated land is a giving back of sorts. Oakland has essentially been able to gather land that will be specifically reserved for Native communities and traditions. Just recently the community was able to plant paw paw trees and Native plants on the land to continue these traditions and ceremonies.

Now that we have a place where Native traditions and practices can flourish once again, we can think about how the land can free Old Indian Legends from the confining Library of Congress catalog. Zitkála-Šá entrusted her future audiences to imagine new ways forward with these stories, integrating them into more than just one culture. When my peer and I identified her signature, we found that she didn’t just sign it Zitkála-Šá; she signed it Zitkála-Šá (Gertrude Bonnin). Acknowledging both sides of her identity, she addresses both Native children and settler descendants. Personally, I think bringing her work onto the land and teaching these stories by reading them aloud, in oral tradition, the way they were taught to her, will bring that history back to life – reviving it in the same way Oakland is reviving the land by having it rematriated. As for the archives and their role in decolonization, it’s vital that the cataloging system be altered in a way that welcomes in Native scholars and authors, allowing new audiences to find these amazing works and learn from Native voices as I did in my class.

- Dornbusch, Erin. “Ginn & Company.” Industry in Cambridge, historycambridge.org/industry/ginncompany.html, Accessed April 5, 2023. ↩︎

- “Thelma James Collection.” Special Collections, OU Libraries, https://library.oakland.edu/collections/special/, Accessed April 5, 2023. ↩︎

- Zitkála-Šá. Old Indian Legends. Ginn & Company Publishers, 1901, Boston, U.S.A, and London. ↩︎

- “Class E-F- History of the Americas.” Library of Congress Classification Outline, Library of Congress, loc.gov/catdir/cpso/lcco/, Accessed April 5, 2023. ↩︎

- O’Brien, Jean M. “Chapter 1 Firsting: Local Texts Claim Indian Places As Their Own.” Firsting and Lasting, University of Minnesota Press, 2010, pp. 1-53. ↩︎

- Long Solider, Layli. “Introduction”. American Indian Stories, Modern Library, 2019, New York. ↩︎

Suggested Readings

- Zitkála-Šá, 1901 Old Indian Legends

- Jean M. O’Brien, 2010 “Chapter 1 Firsting: Local Texts Claim Indian Places As Their Own.”

- Gerald Vizenor, 2008 “1. Aesthetics of Survivance.”

Author Bio

My name is Isabelle Casas and I’m from Eastpointe, Michigan. For the past four years, I worked to obtain my bachelor’s degree in Creative Writing with a specialization in Fiction and a minor in English at Oakland University. Presently, I’m working on a writing/editing career and plan to utilize the knowledge I’ve obtained from Oakland to better promote diversity and inclusion in the publishing industry.